A porcelain gold-plated sculpture of Michael Jackson, giant metallic replica balloon animals and framed vacuum cleaners are among his most celebrated – and most hated – works. He’s famous for rejecting the perceived hierarchy between high and low culture, between child’s “play” and adult’s “art”. In his own words, however, all of it “has been about the viewer more than anything else”.

Walking into the Mayfair Almine Recht gallery and being confronted with, among other things, a giant reflective ballerina gives an instant sense of childish satisfaction. The intrusion of the oversized, imposing (and indulgently tacky) ballerina’s shiny veneer into the white space is delightfully jarring. The paintings that precede it are another story, though. In fact, I’m beginning to suspect I’ve “missed the point” before I arrive at Gazing Ball (Giotto The Kiss of Judas).

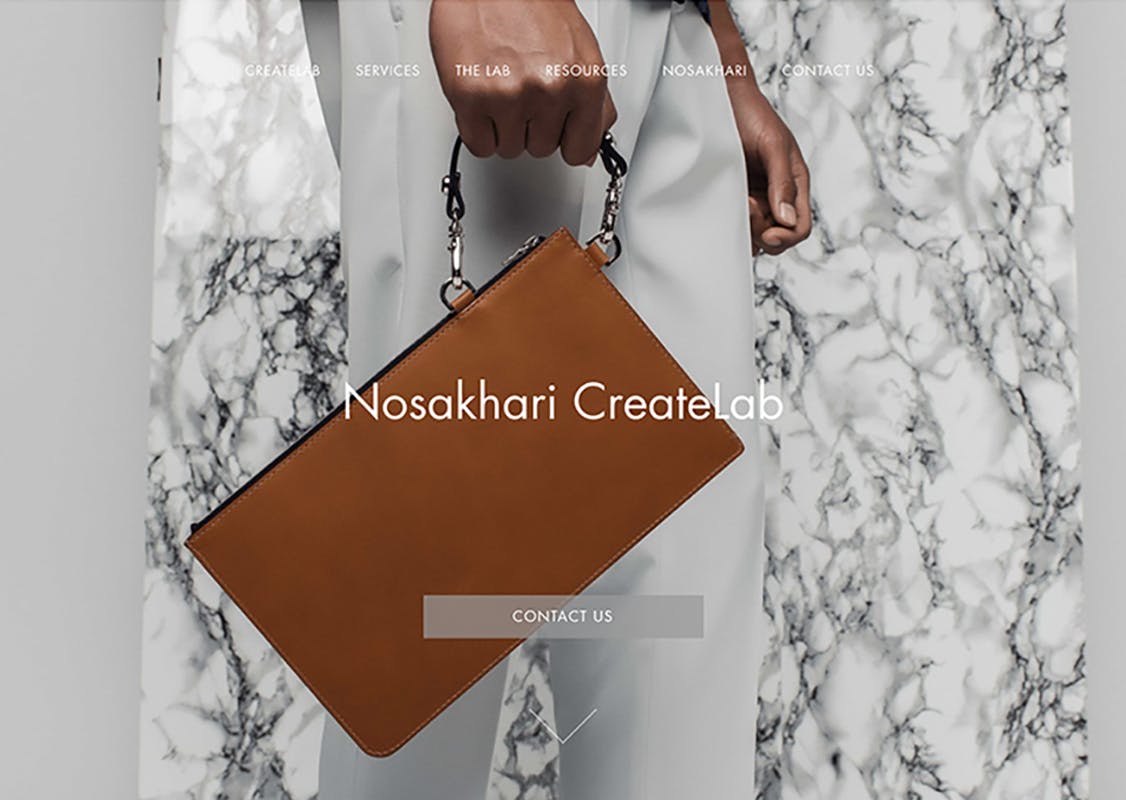

The 2013 “Gazing Ball” series featured casts of features of middle America (garden sculptures, mailboxes and car engines) alongside canonical sculptures of classical antiquity – with a reflective blue bauble attached, reflecting the rest of the gallery and the viewer. The set of works on show here are much more interesting, with specially-placed shelved sprouting from flat printed reproductions of oil paintings. On the one hand, the fact that these paintings are flat immediately reduces them to what Koons refers to as “the idea of a painting”. On the other, this reduction is off-set by the 3-d protruding shelf and ball that draws the painting’s surroundings into it along with the viewer. These uncontoured prints are not meant to be viewed as copies but as re-interpretations of the originals, an engagement with historically-significant art rather than an elevation of it.

Giotto’s 14th Century “The Kiss of Judas” is probably the most famous depiction of the betrayal of Christ by Judas Iscariot, capturing the moment at which Christ is kissed and so identified to the Roman soldiers who would arrest him. While Judas grasps him by his shoulders and envelopes him with his cloak, Christ remains composed and unflinching in the face of the kiss that would be his death warrant. Koons’ gazing ball is balanced on a barely visible shelf jutting from the folds of Judas’ cloak, and it appears to emerge from the central image of the painting – the point of embrace between betrayer and betrayed.

Facing the painting head on, I find myself inserted into the scene through my reflection in the sphere. As much as I am a viewer of the painting, I am now confronted with the image of myself viewing the painting and reflection. Koons makes it impossible for us to forget that we have a gaze as unique as our reflections when considering art. He also invites us to consider how we might participate in the imaged “idea” of betrayal and forgiveness as a real situation. I find myself wondering is what it would take for me to commit a betrayal so complete – or to forgive so calmly. In a world increasingly divorced from the Christian cultures that fostered Giotto’s masterpieces, the insertion of white plaster walls, electric lights and my own face through an alien medium into a key moment of Christian Biblical history doesn’t provide clear direction. It just reminds me that looking at art is as much about considering myself as it is about art.

Gazing Ball (Giotto the Kiss of Judas) (2016), Jeff Koons. © Jeff Koons – Photo courtesy of the artist and Almine Rech Gallery